The International People’s Health University (IPHU) of the People’s Health Movement (PHM) – jointly with PHM-Bangladesh, Gonoshasthaya Kendra, Third World Network, and SAMA Resource Group for Women and Health with Naripokkho – condcuted “THE STRUGGLE FOR HEALTH”- a short training course for young health activists from 6 to 13 November in Savar (just outside Dhaka), Bangladesh. This course was a lead up to the 4th People’s Health Assembly (more here) which was also held at Gonoshasthaya Kendra from 15-19 November.

The course was primarily divided into streams: ‘Access to Medicines’ and ‘Gender, Justice and Health’. Sama was instrumental in bringing to life the latter with objectives to deepen and strengthen networking among and across gender focused activists within and beyond PHM, at the local, national and global levels; strengthen activism around gender and health issues at local, national, and international levels; and establish a stronger understanding of gender and health issues within and across PHM.

The Gender, Justice and Health stream was a four day course within the IPHU on the struggle for Health. It took place at Gonoshasthaya Kendra, Savar, Dhaka, Bangladesh in November 2018. It was organized by two feminist organizations, SAMA from India and Naripokkho from Bangladesh. They also invited other health activists and organizations working in gender and health issues as well as lawyers working in Sexual and reproductive health & rights. The participants attending the course were young health activist coming from different countries such as Nepal, India, Bangladesh, South Africa, Kenya and Spain. This multiculturality among the participants assured, the exchange of experiences and knowledge as well as the creation of networks and collective learning.

In summary, the course began with key concepts related with gender such as patriarchy and the necessity of intersectionality in health research and health programmes (analysis of gender, caste, class, race, sexuality, and disability). It continued with a focus on the reproductive and sexual health and rights, the impact of the medicalisation of bodies through reproductive and advanced bio-technologies, the rising fundamentalisms impacting health (resistance to abortion and sexuality education), gender-based violence and conflicts from a gender lens. The last session of the course focused on the right to health and the role of the women’s movements, as an important element to achieve Health for All.

On the first day key concepts related with gender were shared through different dynamics and groups work. The aim was to build a common understanding of some of the key concepts necessary to develop a gendered perspective. The gender perspective in health requires considering gender inequalities in power, in the access and control over resources, the sexual division of labour and gender socialization. Concepts such as masculinity and femininity, patriarchy, heteronormativity, the sex-gender distinction, the non binary gender identities (queer theory), and the fundamentals of gender equality, gender-based discrimination and gender justice were emphasised.

Afterwards, the group discussed how society constructs and reproduces gender roles within social institutions (family, schools, health system, etc) and the impact this has on health. Gender norms determine different pathways and opportunities for people according to their sex and gender, which are associated with gender inequalities in healthcare. These must therefore be considered in community health interventions and health research. A gender transformative approach is an approach adopted in some programmes and interventions that create opportunities for individuals to actively challenge gender norms and address power inequities between persons of different genders.

Two resource persons shared their experiences; one focused on the narrative of the sex workers movement in Bangladesh, flagging important aspects of sexuality and the convergence of movements. The other, shared the trajectory of the movement against Section 377 in India, which highlighted the struggles of the queer / LGBTIQ movement and the historic judgment on 377. At the end of the day,through a dynamic called ‘The Power/privilege/access walk’ a collective reflection was made about the importance of intersectionality. Intersectionality seeks to be a multi-level analysis that incorporates attention to power and social processes at both micro and macro levels through which subject formation occurs. It also leaves open the possibility of simultaneously experiencing the effects of privilege and penalty, thus challenging binary thinking, which tends to place certain groups in opposition to one another (e.g. women/men; black/white; Aboriginal/non-Aboriginal).

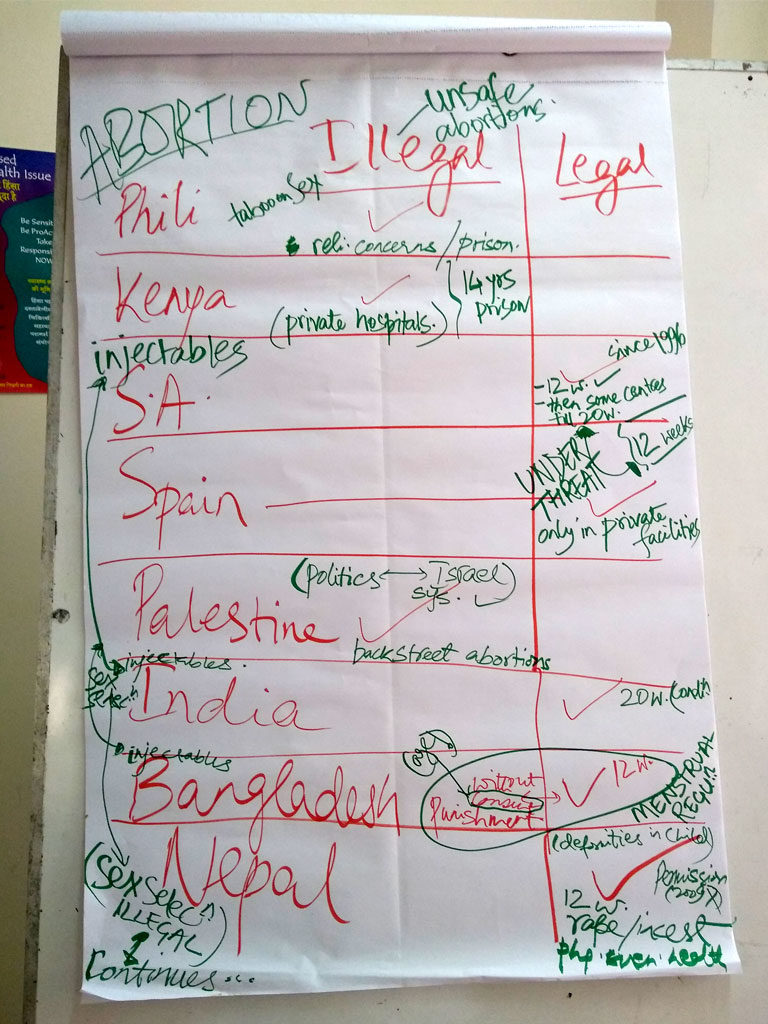

The second day focused on Sexual and reproductive health & rights (SRHR). It started with a historical overview, shifts and trajectory of SRHR, including the concept of reproductive justice. The main International agreements regarding SRHR such as The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) were presented along with the importance of respect, protection, promotion and fulfilment of SRHR.

In the afternoon session we discussed Gender, Health and Technology where we critically examined the interface of health and (new) medical technologies through a gendered perspective. Debates about hormonal contraceptives, commercial surrogacy and Assisted Reproductive Technologies (ARTs) were held. The women’s movement against Norplant (a contraceptive using hormonal implants) in Bangladesh was also presented. A documentary film on the commercial surrogacy industry in India was also screened in order to discuss and understand the overlap of reproductive technology, globalized markets and women’s health & rights.

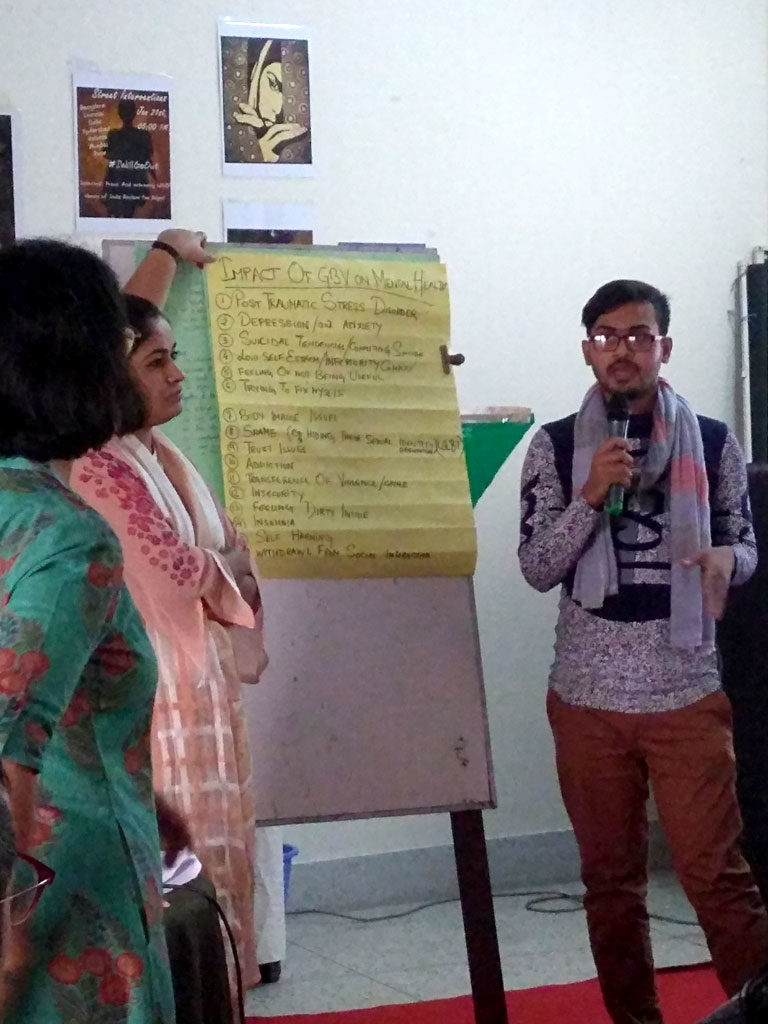

On the third day we addressed the public health problem of Gender Based Violence (GBV). The structural determinants of GBV and its various forms were described collectively. It was highlighted that GBV is a form of human rights violation that severely impinges on the right to health. The groups had a discussion on the role of health systems in mitigating and addressing GBV and different experiences from our different countries were exposed. An activity to emphasise the importance of “listening” to survivors of violence also took place, linking this exercise to systemic gaps and issues – e.g. health system – in acknowledging and responding to women’s narratives, experiences of violence. Regarding gender and mental health, a member of PHM Latin America (Maria Zuñiga) gave a presentation about the importance of focusing on mental wellbeing in the context of violence and conflict. She explained healing practices amongst indigenous communities in Latin America and the gaps in public mental health care.The need for public health measures of healing beyond the bio-medical, as well the need to develop adequate skills and human resources in mental health, was also emphasised.

The fourth day addressed the basic understanding of Conflict, Gender and Health. Through a close look at contexts of conflict, how conflict is experienced in a gendered manner and has immense health consequences was highlighted. Regarding the Palestinian conflict our colleagues explained the history of the occupation since 1948. They also exposed the Illegal settlements and outposts in the occupied territories, the Apartheid Wall and the situation in Gaza(95%of the water is undrinkable, 4 hours of electricity per day, 45% of unemployment, 46% kids suffer anaemia, 45% kids express no will to live, 2 million people denied freedom of movement.) They focused, in their presentation, on the impact of the conflict among children and women.

The current situation of the Rohingya refugees coming from Myanmar was also exposed by health workers working in the refugee camps. A documentary video named “No women’s land” was shown in order to illustrate the situation of Rohingya women in the refugee camps. It highlighted how rape was used as a tool for ethnic cleansing. The Kashmir conflict was also presented through a video focused on the young population. At the end of this session it was highlighted how conflicts severely impact determinants of health and present challenges for access to health care (including psychosocial support).

The last session of the Gender, Justice and Health course was about the importance of the human rights framework in the struggle for health. We started with a group activity in which we were asked to mark the key milestones in human rights and the right to health (laws, policies and actions) at an international and national level, as well as personal experiences in our area of work or part of a health campaign. The participants agreed that the Right to health is not narrow, it encompassed a lot of other rights, freedoms and social determinants that are also related to health such as the right to life, liberty, equality and non-discrimination, bodily integrity, freedom from arbitrary detention, self-determination, identity, freedom from slavery, association, movement, freedom from torture, food, water, housing, social security, education, etc. In that sense, in order to guarantee the right to health it is important to address the underlying determinants (safe food, water, education, etc), freedoms (from torture, from discrimination,) and entitlement (system of health protection, prevention treatment and control, access to essential medicines, maternal child and reproductive health, equal and timely access to basic health services health care system, access to medicines…).

The cross cutting base of ‘health’ as a human right and the right to equality and non discrimination on the basis of gender are established in important human rights instruments, such as the Convention Against All forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW). The concept of ‘substantive equality’ in discussing the interface of gender and health was emphasised. PHM understands health as a reflection of a society’s commitment to equity and justice. Health and human rights should prevail over economic and political concerns. Even if the right to health is upheld by constitutions all over the word it is important for social movements in health to see the relationship with other rights and social determinants in order to struggle in a holistic way. It is important to create networks with other movements working on defending the environment, the housing condition and so on, as all of them are related with the right to health in some way. Finally, some key mechanisms of human rights accountability were exposed, which provide scope of participation by the civil society to hold states accountable on their obligations regarding gender and health. Last but not least we discuss about potential gender and health advocacy agendas for PHM that were further discussed during the PHA4.